The claim that romanticizing or celebrating the Soviet Union has nothing to do with Vladimir Putin, modern-day Russia, or the war in Ukraine has become a reflexive defense among segments of the Western left.

It is repeated as if this weird secondhand nostalgia for the USSR were an aesthetic preference or a form of anti-capitalist sentiment detached from present-day violence.

This separation is fiction. The ideological DNA of Russian imperialism runs directly through the Soviet project and into the rhetoric, symbols, and actions of the modern Russian state.

„Geopolitical Catastrophe” and Trying to Revive Old Ghosts

Vladimir Putin has been explicit about how he feels:

„The collapse of the Soviet Union was the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the twentieth century.”

This line, delivered in 2005 and repeated countless times since, isn’t just nostalgia from a man who built his existence on his time in the KGB. It’s a political framework. It implies that Russia’s natural state is imperial and that its disintegration was an aberration.

In the Kremlin’s lexicon, „catastrophe” refers not to economic collapse or social upheaval (both of which happened and contributed to a transitional period marked by destabilization and hardship), but to the loss of control over non-Russian nations that regained independence in 1991.

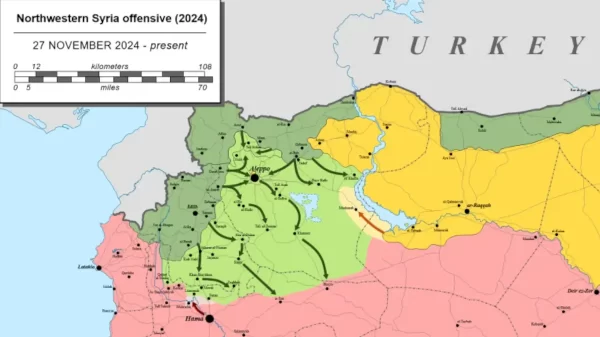

This grievance narrative has defined Russian foreign policy for over two decades. From the wars in Chechnya to the invasions of Georgia (2008) and Ukraine (2014, 2022), each act of aggression has been justified as an attempt to „restore stability” or „protect Russian speakers.” The unspoken premise is that the Soviet imperial space has simply been rebranded as the „Russian world” (Russkiy mir) and Russia insists on maintaining Moscow’s imperial sphere of influence.

Historical Revision as Imperial Doctrine

Putin’s 2021 essay On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians makes the connection explicit. He asserts that Ukrainians are „one people” with Russians, that modern Ukraine is an artificial construct, and that the Bolsheviks’ decision to recognize Ukrainian nationhood was a historical mistake. In his telling, the USSR’s federal structure and its nominal respect for national autonomy were errors that fractured an otherwise „organic” Russian civilization.

This is nothing new. It simply echoes 19th-century imperial discourse, when Tsarist officials referred to Ukrainians as „Little Russians” and denied the existence of a separate Ukrainian language or culture. By invoking the Soviet Union’s internal borders and „gifts” to Ukraine (notably Crimea, according to Russia), Putin collapses imperial and Soviet histories into a single continuum of rightful Russian domination.

When he declared in February 2022 that Ukraine is „not just a neighboring country for us, but an inalienable part of our own history, culture, and spiritual space,” he was restating an old colonial principle: that the empire never truly ends where its armies once stood.

In June 2025, he repeated this sentiment at an economic forum in Saint Petersburg, saying, „I’ve said it before, Russians and Ukrainians are one people. In this sense, all of Ukraine is ours. There’s an old rule that wherever a Russian soldier sets foot, that’s ours.”

Weaponization of Soviet Symbolism

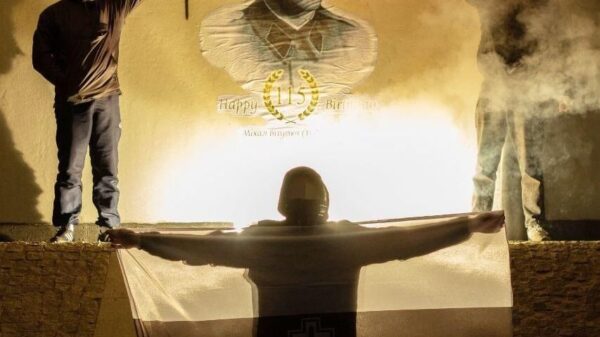

Soviet imagery has re-emerged as a core element of Russia’s military and ideological apparatus. You can find it on tanks and on the uniforms of soldiers committing war crimes. Hammer and sickle flags have been raised in occupied territories where people are forced to adopt a Russian passport or face torture, deportation, or death. Russian soldiers film themselves raising the Soviet banner atop ruins, attempting to echo the 1945 photograph of the Red Army over the Reichstag in a deliberate recreation meant to frame invasion as liberation.

In occupied territories, Soviet monuments destroyed during Ukraine’s post-Soviet era of independence have been rebuilt, while Ukrainian memorials are erased. School curricula reintroduce Soviet-era „patriotic education.” Streets revert to their Soviet names. This is not simple innocent nostalgia.

The Kremlin’s annual „Immortal Regiment” marches, ostensibly commemorations of WWII, have become rituals of militarized state identity by blurring past and present, implying that to fight in Ukraine is to finish the Great Patriotic War.

The Western Left’s Selective Amnesia

Factions of the Western left continue to excuse or romanticize the Soviet Union, framing it as a counterweight to Western imperialism or neoliberal capitalism. In this narrative, the USSR is remembered as a noble experiment, its crimes downplayed as unfortunate „mistakes” or denied entirely. That same logic now shelters Putin’s Russia under the illusion of „anti-imperialist multipolarity.”

Writers, academics, and activists who share memes of Soviet culture or factory murals, who praise Soviet urbanism or „socialist modernity,” or who blatantly cling to Soviet symbols from the comfort of their western homes often insist that such appreciation has nothing to do with Russian aggression. But they’re cherry-picking aesthetics from an empire built on deportation, Russification, and political terror.

One cannot romanticize the Soviet Union without romanticizing the power structure that suppressed nations from the Baltic to Central Asia. And it’s precisely the structure Putin seeks to resurrect.

To uphold Soviet symbolism while condemning Russian imperialism is like mourning the British Empire’s fall while claiming to oppose colonialism. The two are not separable.

The continuity between Soviet nostalgia and modern Russian aggression is undeniable. The Kremlin has institutionalized reverence for the USSR, waging wars in the language of historical restoration while appropriating the language of antifascism to legitimize acts of conquest.

Western admirers who indulge in Soviet romanticism, even aesthetically or unknowingly, obscure this reality, allowing imperial myths to masquerade as liberation. To dismiss the link between Soviet nostalgia and Russia’s actions is to erase the lived histories of nations that endured both Soviet and Russian domination. From Prague to Vilnius, from Tbilisi to Kyiv, this flag no longer signifies socialism; it signifies tanks in the streets, erased independence, and ongoing occupation.

Radical Dumpling